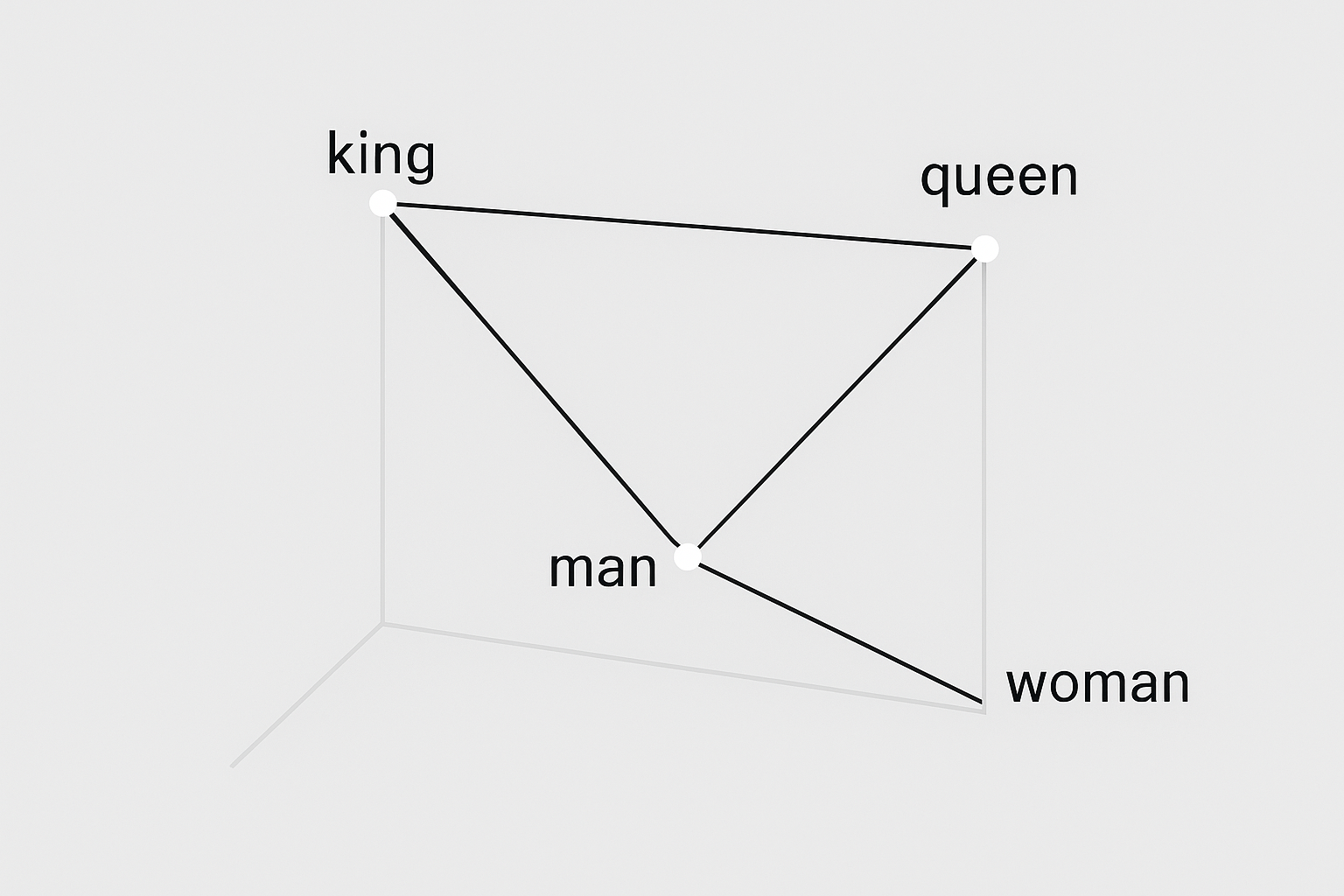

Before Word2Vec, representing words for ML was painful. One-hot encoding treated every word as equally different. TF-IDF captured some statistics but no meaning. Then in 2013, Mikolov and team at Google published Word2Vec, and suddenly we could do things like:

king - man + woman ≈ queen

Wait, what? Word arithmetic that actually works? Let’s see how.

The brilliant insight

Words that appear in similar contexts have similar meanings.

Think about it: “dog” and “cat” both appear near words like “pet”, “cute”, “fur”, “feed”. The word “laptop” appears near totally different words. So if we train a model to predict context, “dog” and “cat” vectors will naturally end up close together.

The embeddings aren’t the goal - they’re a “side effect” of training a simple prediction task. And that side effect turned out to be incredibly useful.

Interactive demo: Word2Vec Animation - see how word vectors organize themselves during training.

Two training flavors

Skip-gram: Given a center word, predict the surrounding context words

"The cat sat on the mat"

Center word: "sat"

Predict: "The", "cat", "on", "the"

CBOW (Continuous Bag of Words): Given context words, predict the center

Context: "The", "cat", "on", "the"

Predict: "sat"

Which is better? Skip-gram works better for smaller datasets and rare words. CBOW is faster and handles frequent words well. In practice, Skip-gram is more popular.

The architecture (surprisingly simple)

It’s basically just one hidden layer:

- Input: one-hot encoded word (vocabulary size V)

- Hidden: embedding dimension (typically 100-300)

- Output: vocabulary size V, with softmax

Input (V) → Hidden (D) → Output (V)

The hidden layer weights ARE your word embeddings. That’s it!

Negative sampling

Don’t compute full softmax. Instead:

- Real context pairs: positive examples

- Random word pairs: negative examples

Only update weights for these few words per example.

# pseudo-code

for center, context in training_data:

loss = -log(sigmoid(dot(center_vec, context_vec)))

# add k negative samples

for neg_word in sample_negatives(k):

loss += -log(sigmoid(-dot(center_vec, neg_vec)))

Much faster. Quality nearly as good.

The famous analogies

“king - man + woman = queen”

This actually works (roughly). Vectors capture semantic relationships.

# assuming we have word vectors

result = model['king'] - model['man'] + model['woman']

most_similar = find_nearest(result) # returns 'queen'

Practical considerations

Window size

Smaller (2-5): captures syntactic similarity Larger (5-10): captures topic/semantic similarity

Embedding dimension

More dimensions = more capacity but slower and needs more data Common: 100-300 for most applications

Minimum count

Words appearing < N times get filtered. Rare words don’t have enough context to learn good vectors.

Training your own

from gensim.models import Word2Vec

sentences = [["the", "cat", "sat"], ["the", "dog", "ran"]]

model = Word2Vec(

sentences,

vector_size=100,

window=5,

min_count=1,

sg=1 # skip-gram

)

# get vector

cat_vec = model.wv['cat']

# similar words

model.wv.most_similar('cat')

Word2Vec intuition unlocked? Consider starring ML Animations and spreading the word on social media!